Mergers and acquisitions trends for 2025 and beyond

It’s been the best of times and worst of times for mergers and acquisitions. As volume and valuations rose in Q4 of 2024, it was expected that the New Year would bring a resurgent M&A market. The potential for cheaper borrowing costs and less regulation fueled a rally in January.

But the party may be over, at least for now. With the prospect of tariffs, government austerity measures and contracting GDP, the threat of volatility may be worse than volatility itself. Headed into the year, the market had priced in a 100-basis-point decline in interest rates this year, but Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has been accused of being someone who comes late to parties.

Headed into 2024, deal flow and multiples had been well below their 2022 highs. One of the reasons valuations had stalled is that private equity has been on the sideline. With fewer financial buyers, private seller auctions have been somewhat limited to strategic buyers. While volume was strong for bigger companies, deals for SMBs (small and midsize businesses) shrank by 18% in 2024.I

The uncertainties about tariffs and federal spending impact the valuation of the dollar, the balance of imports and exports, and the likelihood of another round of supply chain shocks. In many cases, SMBs do not feel confident paying 6-10X to roll up similar firms. And as companies are distracted by operational challenges posed by tariffs and other market shifts, they may be less focused on mergers and acquisitions.

As many economists revise down their GDP growth forecasts for 2025-2026, multiples could erode further.

Key factors impacting mergers and acquisitions

Sector shifts

The new administration may spark headwinds in some industries and tailwinds in others. In energy, for example, investment is likely to shift from renewables to more traditional oil and gas. Shifts in infrastructure spending may redirect sectors such as public works construction toward data centers and chip manufacturing.

It is a bit early to see the true impact of tariffs, and if they represent a fundamental shift in trade policy versus a negotiating tactic, but U.S. manufacturing is likely to rebound. It will also take time, as companies reinvent their supply chains.

Private equity on the sidelines

While PE total assets under management swelled to a record $3.5 trillion in 2024, they still held over $1 trillion in dry powder. PE investments represented 42% of deal flow in January. That is on the heels of a stronger showing in 2024 when PE deal flow increased by 12.8%.ii

Source: Forvis Mazars Capital Advisors

However, that was coming off a poor showing in the prior year, and there was heavy concentration in sectors such as life sciences and energy. To some extent, the most natural roll-ups occurred before the pandemic, and PEs are having a harder time justifying investment.

Vertical integration

The last five years have seen a resurgence in vertical integrations. For example, the recent deal between Rocket Mortgage and Redfin would combine real estate brokerage, mortgage, title and other transactional capabilities under one roof. This is a subplot in a clear trend towards more bundling.

Banks sell all types of insurance and investment services. Accounting firms will now be allowed to offer legal services. The U.S. health care system is completely integrated, with physician groups, hospital systems, insurance companies and pharmacy benefits managers providing a web of services.

Once the domain for public companies, vertical business combinations are now an opportunity for SMBs. Such combinations will offer synergies of integrated systems, deeper data analysis and efficiencies that reduce labor and accelerate transactions.

International economies in flux

While the U.S. economy feels volatile, it’s still considered a safe harbor. Headed into 2025, forward PE for U.S. S&P stocks was 23, compared to publicly traded stocks around the world which were trading at 14.iii

While the U.S. economy is trying to reconcile the chaotic implementation of tariffs, the pain is likely temporary. Peace in Ukraine and the Middle East is nebulous at best. Other economies around the world face problems with economic fundamentals, including declining population growth, high energy costs and slow growth.

Europe’s economy appears stuck in quicksand. European companies have provided more regulatory oversight over tech companies and are not participating in the AI boom, as the U.S. and their Asian counterparts have.

The emerging role of debt

The 10-year Treasury traded close to 5% earlier in the year, which many consider the milestone that triggers outflows from equities. Also, the debt issuance in the U.S. and European high-yield bond markets was up 74% to $388 billion in 2024.iv

Many private equity firms have shifted their attention to the private credit market. For example, BlackRock announced its intention to purchase HPS Investment Partners’ private and public credit business for approximately $12 billion.

Technology’s role in dealmaking

A maniacal focus on technology (especially AI) is causing a shift toward entirely new business models. Companies are looking for AI to extend beyond improved productivity, reshaping value creation. One could argue that technology firms have an advantage as they move toward a “digital core.” It’s also possible AI could be the great equalizer for smaller companies who figure out how to unleash its transformative power.

Changes in compliance

While it’s presumed that the change in administration would support less regulation, there’s an even more fundamental reset occurring in how the federal government will oversee the U.S. economy. A changing of the guard in the Federal Trade Commission is, on its face, less burdensome, but early indicators are that the new FTC will maintain policy regarding illegal trade practices that restrict competition.

The playbook for sellers

Sellers should consider the following factors in planning an exit:

Timing is everything. 2025 may not be a fertile time to sell. If you subscribe to the predictions by many economists (including those at ITR Economics), the market could erode in the next 5-7 years. There may be a window when rates come down, and PE firms return, resulting in a higher valuation in two to three years.

Partner with international firms. Often, strategic alliances turn into acquisitions. Foreign companies, saddled by poor growth at home, may look to invest in U.S. companies to reduce their risk.

Be the safe choice. Companies that have achieved market leadership and have strong balance sheets are the most valuable. The top criteria for buyers are recurring revenue, revenue growth, employee turnover (or the ability to retain a strong management team), margins and concentration risk.v

The playbook for buyers

For buyers, a clear playbook is emerging.

Understand shifting supply chain fundamentals. These extend well beyond companies nearshoring. There will be imbalances in supply and cost, and those who close these gaps through vertical integration or other measures will have a competitive advantage.

Go international. The dollar has slipped in recent weeks, but it remains very strong relative to other currencies. This provides U.S. companies the opportunity to acquire businesses abroad at a discount.

Focus on quality. Companies with strong financial statements are receiving a significant premium. As Warren Buffett once said, “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

References

i PWC 2025 Global M&A Industry Trends

ii Forvis Mazars Capital Advisors

iii Guru Focus

iv PWC 2025 Global M&A Industry Trends

v First Page Sage

Related Resources

Vistage Transaction Center [[password req’d]

Mergers and acquisitions trends for 2023 and beyond

Amid the economic uncertainty and changes in corporate priorities, patterns in mergers and acquisitions are changing. There is a clear shift toward conservatism. Given the high cost of debt, deal flow has moved toward restructuring, including spinoffs and smaller deals with less risk. i

There are also structural, permanent changes to how businesses are valued. In the past, companies mostly focused on growing top line, entering new markets, and reducing the number of competitors. But today, dealmakers are looking to transform their businesses through new business combinations. Digital transformation technologies, and in particular artificial intelligence, are bringing buyers to the table.

Valuations have not yet recovered from the pandemic

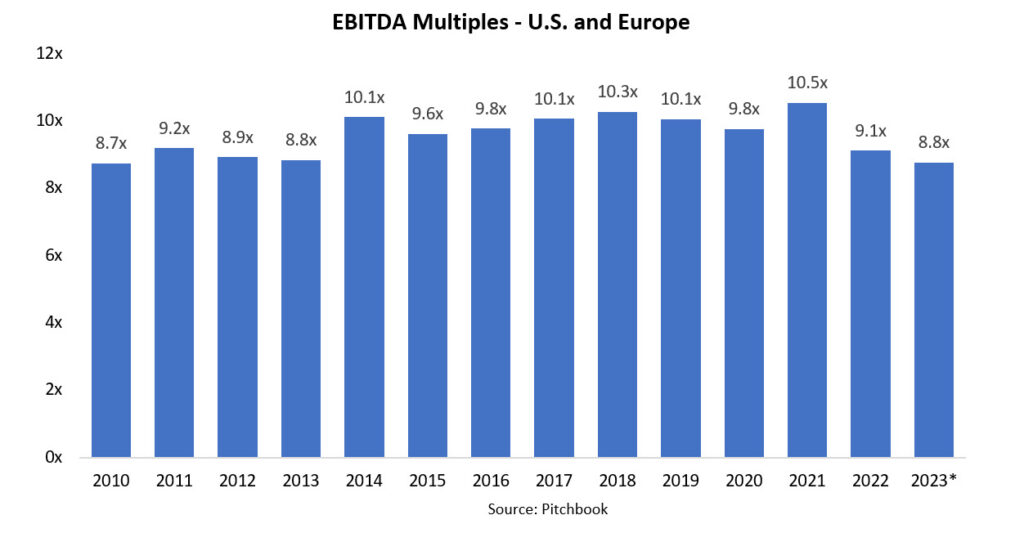

Given the economic headwinds, valuations have declined in the U.S. Through March, Pitchbook reported EBITDA multiples of 9.1, down one full turn from 10.1 in 2019, when multiples peaked. Deal counts increased in 2021 and 2022 over prior periods. Q1 2023 deal counts were down (valued at about $1 trillion) amid widespread discounting.

Private equity takes center stage

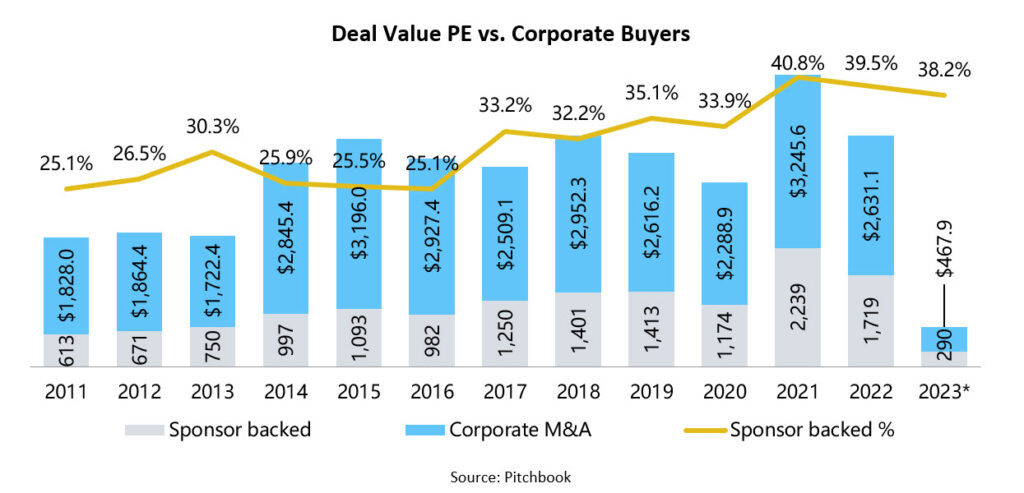

Private equity (PE) firms still have $3.7 trillion of dry powder on the sidelines. ii As their compensation is tied to deploying capital, PE partners are highly incented at a time when corporate buyers are pulling back the reins. “Strategics” (corporate buyers) used to pay a premium, but today PE firms often pay more, now accounting for 38% of total transaction value. In 2022, the average PE multiple paid was 11.7, and 8.5 for strategics.

They are also more active buyers. According to MergerMarket, 64% of private equity investors plan to make four or more acquisitions in the next year, compared to 34% of corporates. PE firms are resisting selling off portfolio companies at lower deal values, with PE divestures down 25% in 2022.iii

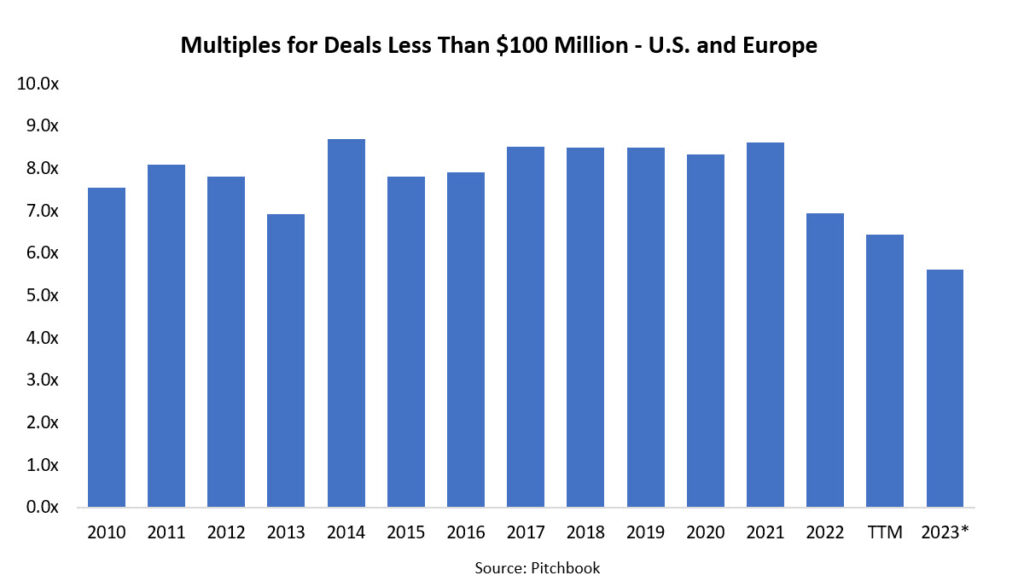

The size premium

While multiples have slid across the board, multiples for mid-market deals are only slightly lower, where deals of <$100 million were down from 8.5x in 2019 to 6.9x in 2022. Conversely, public company values in mergers and acquisitions dropped around 25% in 2022. It’s important to note that average deal multiples are valued differently than traditional stock market price-earnings ratios.

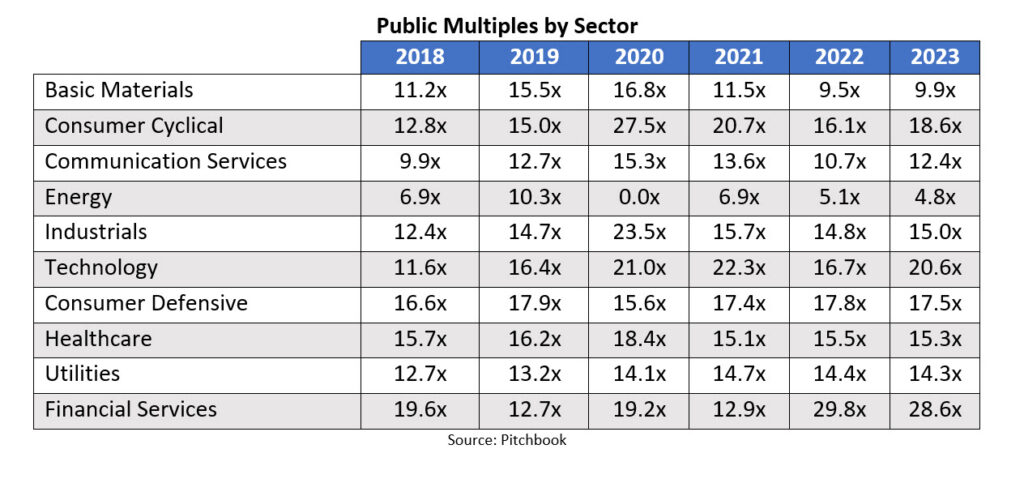

Technology remains hot

Technology continues to be an outlier. In public companies, large-cap stocks continue to outperform. Apple’s enterprise value at points this year exceeded the value of the entire Russell 2000 Index.

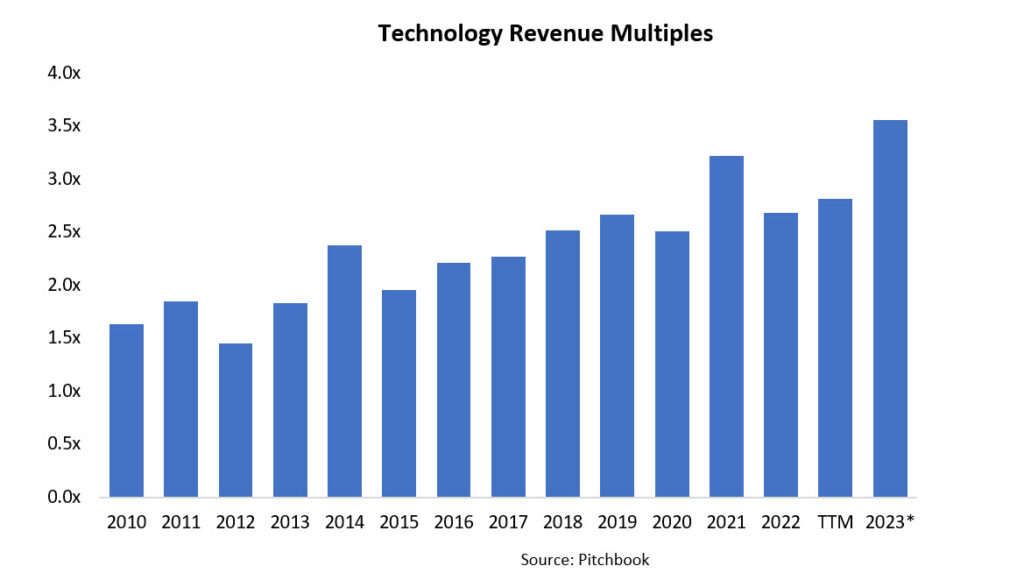

Given the influence of software-as-a-service (SaaS), fintech, and other high-value businesses, more and more industries are being valued using revenue multiples over EBITDA multiples. The 12-month trailing revenue multiple for technology firms is a staggering 2.8, highlighting how the influence of digital transformation, and in particular AI, is moving the needle on valuations. IT and healthcare are growing as a percentage of deals and deal value. In Q1 there were 8 deals over $1 billion, led by PE firms who are very active in the sector, often paying a premium over market valuations.

Sector trends

- The banking crisis had little impact on the broader M&A market, although there was a pullback in financial services deals. iv

- Healthcare (trading at 11.5x EV/EBITDA in 2022) is slumping as providers try to recover from COVID-19 at a time when revenue is fixed, and labor costs are higher.

- The share of B2B deals is up slightly, with B2C deals declining. E-commerce brands are having a hard time maintaining margins amid compressed pricing. Prices are down around 30% from their highs.

- The energy sector (8×2 in 2022) remains highly volatile amid many carve-out deals. BP’s purchase of TravelCenters of America reflects the latest in a long list of vertical integrations across mergers and acquisitions. Yet ebbs and flows in oil and gas, and a fractured shift toward renewables are creating a chaotic market.

- Commodities remain highly cyclical, and some investors shied away, choosing more defensive positions.

- Professional sports franchises are fetching large deals, with Dan Snyder’s $6.05 billion sale of the NFL’s Washington Commanders being the largest in history.

- ESG has accelerated as a consideration in M&A activity over the last year. While public companies have been aware of their responsibilities for some time, private companies are taking stock of the ESG policies of companies they buy.

- Cross-board deals by U.S. firms are slowing, in part due to a declining U.S. dollar.

Market timing

When is the perfect time to buy or sell? It’s hard to catch a falling dagger. Cash-rich companies will seek opportunities to buy weakened competitors and invest in technologies that will drive competitive advantage.

There is likely to be a sweet spot between 2025 when interest rates are lower, and 2032 when the federal debt is likely to result in economic turmoil. Make sure your strategic plan considers both acquisition and divesture scenarios.

References

i Deloitte 2023 M&A Trends Report

ii High PE Dry Powder Sustains Amid New Market Outlook by Allvue Systems

iii Pitchbook Global M&A Report

iv Pitchbook Global M&A Report