Operationalizing Your Strategy: Part 1 of 2

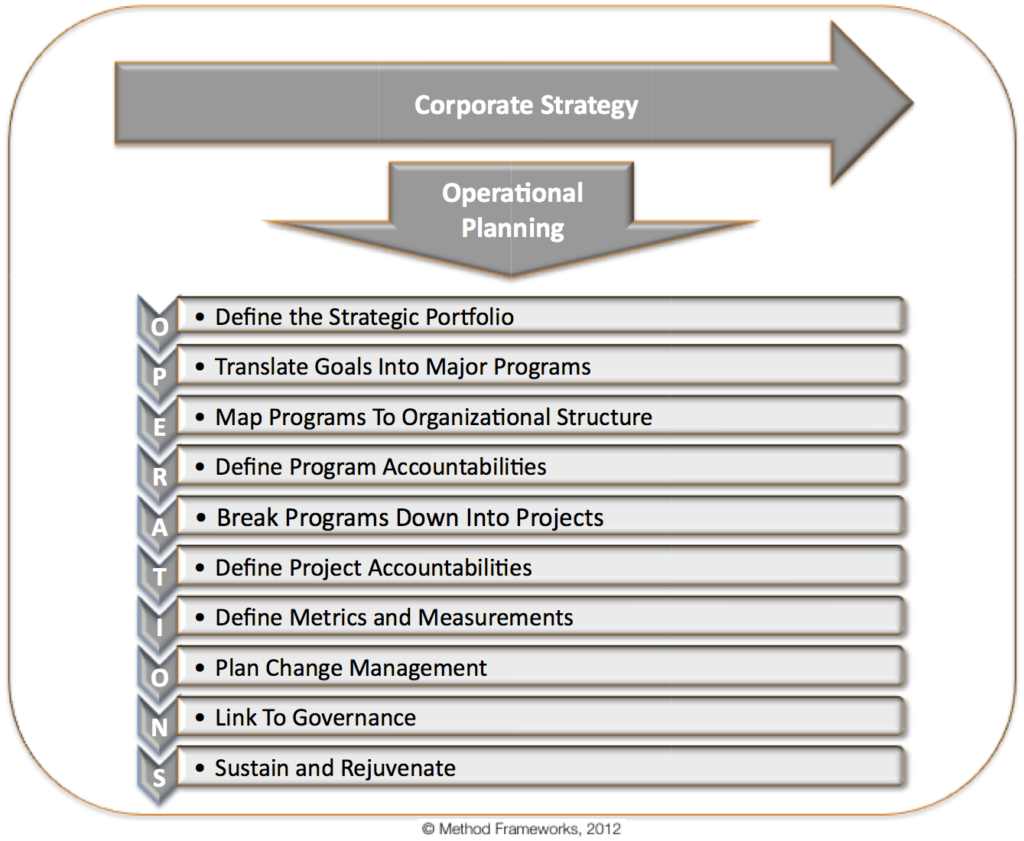

“We are not good at execution.” Could that statement likely come from someone in your organization? Odds are, it has already. Comments like this are not unusual when frustrations with strategy implementation reach the boiling point. Even companies that do a reasonable job at defining strategy and doing high-level strategic planning tend to fizzle out before they get to operational planning. That is unfortunate, because operations-level planning is the essential connection between corporate strategy and the execution of that strategy within the organization. It is the phase of strategic planning really counts the most. Given its importance, understanding how to do operational planning and actually making sure it gets done is well worth the time and effort. This article looks at operational planning in terms of practical steps that businesses should follow to enact execution of their strategies.

Operational planning may not be the sexiest part of corporate strategic planning, but it is one of the most important. Second to actually having a strategy, “operationalizing” it in the business takes second place in the hierarchy of importance. Most companies would receive a failing grade for their operational planning efforts. This is largely due to a lack of understanding of how such planning should be done.

It’s not that operational planning is that complex to carry out, but there is some art to doing it well and it does require finesse. In short, operational planning requires a different skill set and discipline than its counterpart – strategic planning. The biggest difference is that we must adjust our thinking to the day-to-day business operations and consider all the constraints, inhibitors and accelerators that must be evaluated and factored into tactical planning. The discipline required is a mix of strategic planning with good old fashioned program and project management.

In this article, we will explore the first five of 10 basic constructs of operational planning.

1. Define the Strategic Portfolio

The work behind executing a corporate strategic plan lies in the goals that must be achieved. Each of those goals must be understood in terms of the various initiatives the goals really represent. This is a way to understand the work to be done in real terms that apply to business operations.

2. Translate Goals Down Into Major Programs

Translating goals into major initiatives is the beginning of operational plan development, accomplished by mapping the goals laid out in the strategy to chunks of work. The next step though is to bundle or group initiatives into goal-aligned programs. This exercise makes the work to be accomplished easier to understand, manage and track.

3. Map Programs To Organizational Structure

With grouping of initiatives into programs completed, the question becomes, “How do initiatives impact the organization?” Profit and Loss accountabilities, organizational structures and resource control must all be understood as they relate to the strategy programs. Where will resources need to be shared? How will program funding effect budgets across the organization’s structure? This step requires an understanding of organization, its culture and budget controls.

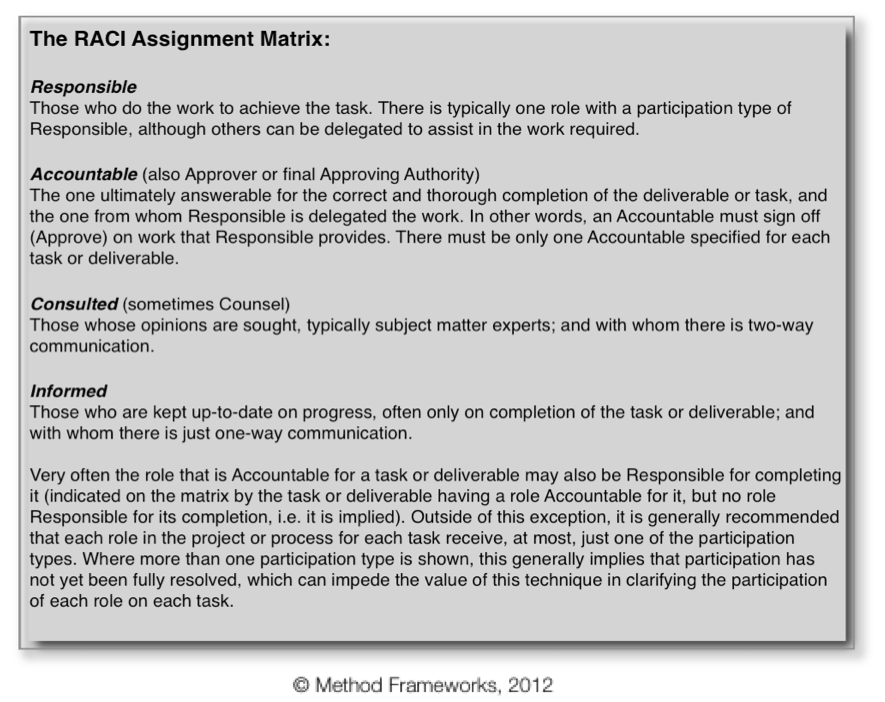

4. Define Accountabilities For Programs

Accountability also must be clear in terms of expected timeframes. For accountability to exist, all who are affected by the plan must understand what is to be accomplished and within what timeframe. After all, it is impossible to hold people accountable for accomplishing a key outcome if there is no basis to measure. Similarly, if an objective that is not bound by time or if the team has unlimited time to complete it, the goal can never be considered to be complete or its progress evaluated.

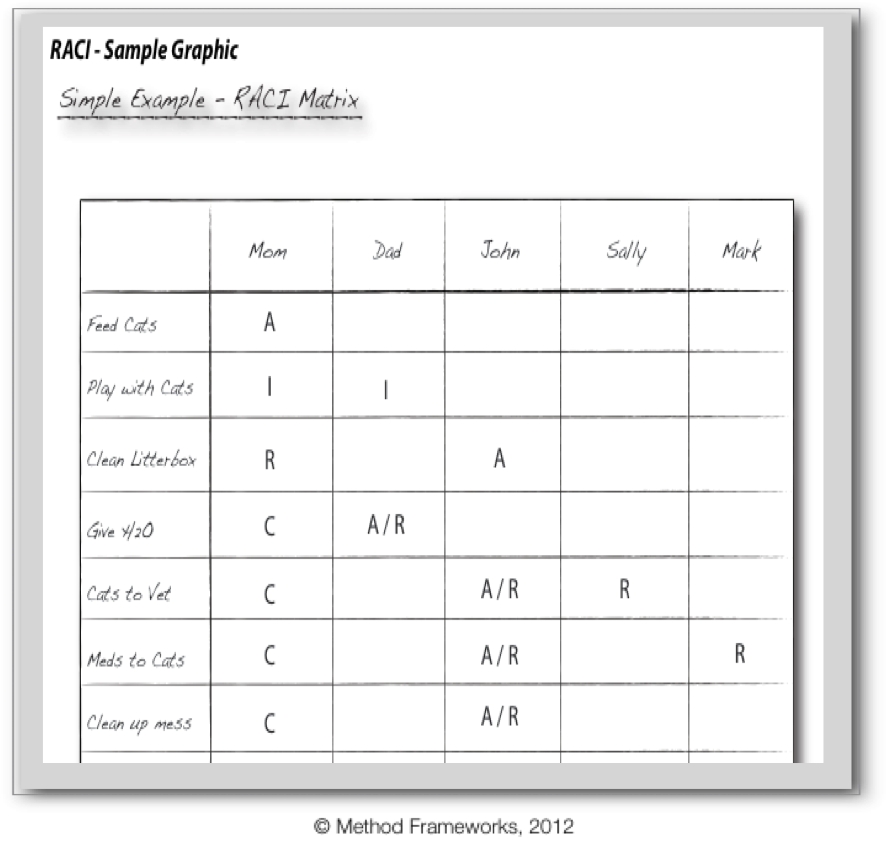

Tools such as RACI models can aid in mapping out Responsibility, Accountability, Consult and Inform roles relative to the programs or initiatives supporting the plan.

5. Break Programs Down Into Projects

5. Break Programs Down Into Projects

Operational planning is all about reality and execution, so estimating work effort and time-to-complete correctly for chunks of work is important. Programs are large and too unwieldy to be estimated and managed without breaking down the effort into smaller chucks, in this case, projects. Project-sized chunks of work can be more easily estimated, resourced and managed.

Projects that have been identified can now be planned for at the detailed level, including: timeframes, human resource requirements, technology requirements and in many cases, dependency on other projects or programs (groups of projects). Careful attention to detail at this level can help avoid collisions with other projects down the line. Even then, there may be inter-dependencies between these groupings of initiatives and shortages of resources where overlaps exist. Tactical planning must delineate to the maximum extent possible the timelines, dependency relationships, resource allocations and costs relative to the allocated budgets across operational areas to avoid as many collisions and conflicts as possible.

Conclusion

Even companies that do a reasonable job at defining strategy and performing high-level strategic planning tend to struggle with operational planning. The first step in operational planning is understanding strategic goals in terms of the various initiatives they really represent. The next step though is to bundle or group initiatives into goal-aligned programs. With grouping of initiatives into programs completed, the next step is to map initiatives to the organization’s structure in terms of impact, control and likely accountability for execution.

Accountability requires clarity. Clarity regarding roles and responsibilities relative to plan goals requires people who have sufficient incentive and understanding to execute to that plan. Employees that understand what is being done, the reasons why, when to do what, and how they can contribute become empowered team players.

Programs are large and too unwieldy to be estimated and managed without breaking down the effort into smaller chucks, so projects must be identified within the programs. Project-sized chunks of work can be more easily estimated, resourced and managed.

In the next segment of this two-part series, the final five basic constructs of operational planning will be explored. In the meantime, see more articles on operational planning at MethodFrameworks.com.

Category : Business Operations